|

Historical Retrospective on Warsaw's German Past

On the other hand, anyone walking through Warsaw for the first time will certainly not get this impression. Warsaw appears to be neither a German nor a typically Polish city, but rather a major international center not characterized by architectural or urban style determined by any particular national tradition. Yet even so, an attentive observer strolling through the city will repeatedly come across buildings whose style strikes him as familiar. And not without reason: a great many of the city's most impressive buildings had their origins in German influence; and similarly, the history of Warsaw as a whole has a strikingly large German component – even if much of it was later covered up. This influence is evident and provable from the very founding of the city onwards. The city was founded in the 13th century under Kulm Law, a variation on Magdeburg Law, known to have been the decisive authority for centuries for almost all cities in the East. Warsaw was still quite insignificant at that time; the capital of the region, for the time being, was Plock, located farther north, and later Czersk, some 30 km. south of Warsaw. Eventually the seat of the duchy of Mazovia gravitated to the region's center, that is, to Warsaw. The German role in this development is unmistakable, as the colonizing immigrants came from the north. The region of Mazovia was at that time the political focus of the Knights of the Teutonic Order.1 Further, the national weakness of Poland – which by the 13th century had broken up into partial principalities – eventually forced Duke Konrad I to call the Teutonic Order into the region of Kulm in defense against the pagan Russians. Among the Teutonic Knights in Konrad's service at that time was the knight Gothard who beat back the invasion of the Jadwingers east of Warsaw, in Podlachia. As reward for this deed, which provided Mazovia with much-needed security, Konrad bestowed on Gothard the town of Sluzewo, whose location is documented more precisely as "in districtur Varsaviense"; incidentally, this same document, dating from 1241, is the first ever to mention Warsaw. It is significant that this happened in conjunction with a deed by which a German knight rendered a great service to the Vistula region. German influence became even more apparent in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. This was the period of ascendency of the Bourgeoisie, during which time Warsaw also experienced that further development which eventually made it the Polish capital city by the end of this period. As early as the 14th century, Warsaw had a constitution providing for a mayor, county bailiff, councilors and jury service, in other words, those German legal institutions that were also the chief pillars of community administration in other German cities in the East, such as Posen, Thorn, Gnesen and Cracow. No less than 78% of the names recorded in those contemporaneous documents which have survived to our times are purely German names – which shows how strong the German influence in Warsaw was at that time, even in terms of the population itself. In the early 15th century, German immigration to this area was particularly great: by 1420, no less than 84% of the names were German. But then immigration from the Empire dropped off significantly. The court documents from old Warsaw for the period 1427–1452 contain only 28% German names.

Just how strong this German influence was during that decisive period of Warsaw's history is still evident today in one of the city's main attractions: the Old Market Square.

The best-known of the old-established bourgeois families is the family Fugger, of the ancient merchant dynasty from Augsburg, which at that time also maintained trading posts in Cracow and Warsaw. Georg Fugger had been the first to move to Poland, and so became the founder of the Polish branch of the family which was active in Warsaw for over 400 years and whose last scion still lives in Warsaw today.

Thanks to these German patricians, Warsaw soon advanced from its existence as small medieval town to the station of major trading city, and in 1569 even rose to the status of Polish parliamentary venue – and thus to de facto capital city, even if its final promotion to official capital did not happen until 1596, when the Royal Castle in Cracow burned down.

In that century, Warsaw expanded southward along what is today the suburb of Cracow, as well as westward to today's Krasinski Square. In the area of today's Cracow suburb, the great castles of the Polish nobility were built, such as for example the Potocki and Radziwill Palaces, whose conception and structure go back to that of a country seat.

Near the end of the 17th century, another German, Christian Eltester, built the charming little castle in Belvedere Park which, however, was extensively rebuilt later. But the apex of cultural creativity in Warsaw came during the time of the Electors of Saxony August II and III, who simultaneously served as kings of Poland from the late 17th century (1697) into the 18th century. Considered from the point of view of overall German history, the Wettins' interlude on the royal Polish throne was no great political achievement, but in terms of cultural history, the influence of these princes had extraordinarily beneficial consequences for the configuration of Warsaw, and for the creation of great and magnificent buildings. During the reign of these two Saxon kings, a restructuring of urban Warsaw was undertaken, since the kind of random, haphazard construction of buildings that had been the custom in the previous century threatened to result in a disaster of urban planning. The "New World" was therefore created by means of a connection with the suburb of Cracow, and extended into a wide avenue, today's Victory Avenue, Warsaw's most beautiful thoroughfare.

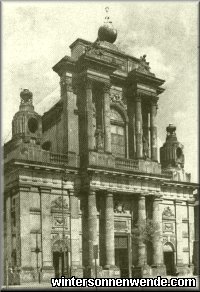

In addition, one must consider the great buildings and renovations which date from those times and which still bear witness to the artistic of Dresden. Pöppelmann, Knoebel, von Deybel, Knöffel, Kammsetzer, Schuch, Aigner, Plersch – those were the pre-eminent architects of that epoch, and their very names, quintessentially German, are proof that the architecture of that time was thoroughly German. It would not be an exaggeration to say that almost all of the Baroque and Rococo architecture in Warsaw is of Saxon origin.

In 1750 Count Heinrich Brühl, Plenipotentiary Minister August III, bought the palace next to the Saxon Palace and also had it renovated in Saxon Baroque style. This building, which still bears the name "Palais Brühl" in memory of its former remodeller, is one of the most important cultural-historical monuments to those times. It is credited to the German architects Knöffel and Knoebel.

The influence of the Saxon architects also extended to the churches, as well as to the palaces of the Polish nobility. These magnificent buildings were created during the reign of August II and August III, and Potocki Palace and Radziwill Palace were among the most noteworthy of them. The Castle itself was also rebuilt, and again one of the family Pöppelrnann – the son of the builder responsible for the Dresden Zwinger* – played a decisive part in its remodelling. The influence of German intellectual life was also extraordinarily strong at that time. German newspapers, a German library, a German academic association and a German literary society grew up in Warsaw and impressed a German character on the intellectual life of that time. In Warsaw's theaters as well, performances were given of Lessing's great masterpieces "Emilia Galotti" and "Minna von Barnhelm".

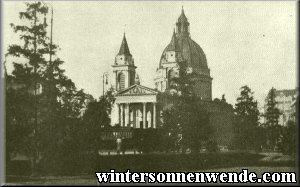

Lazienki Castle was built at that time, and an Italian by the name of Merlini and the court architect Kamsetzer, by birth a German from Dresden, performed the most significant parts of the work, while Ignaz Plersch, also of German origin, had a decisive part in the interior decoration and furnishing of the palace. The park surrounding this summer palace was also designed and created by a German, the landscape architect Johann Christian Schuch, who made a name for himself in landscape gardening in Warsaw.

Here as well, two German architects were of considerable importance – S. Gottlieb Zug of Merseburg, the builder of the Protestant church, and Efraim von Schröger of Thorn [now called Torun], who carried out the renovation of the Carmelite Church, among other things. Peter Aigner also lived in Warsaw at that time;

These names show just how much the influence of the Saxon epoch lingered, even after the Polish had taken over power. Polish political rule lasted only a short time after the Saxon kings had left the scene; after the third partition of Poland, the year 1795 already marked the beginning of the Prussian Era (1795–1806), during which time Warsaw was the capital of southern Prussia. In terms of urban development, the most significant achievement of this time was the "standardization of architectural conditions and urban planning". Before, palaces of the nobility and the lowliest of hovels had been built side-by-side. Order was now brought into this stylistic chaos and confusion. A good number of ordinances and edicts effected typical Prussian planning, which in fact seemed like an anticipation of the many regulations of building control departments of modern times. Stream regulation of the Vistula was also begun for the first time. E.T.A. Hoffmann, Fichte and Seume are but three of the many eminent men who lived in Warsaw at that time. When Warsaw became part of Russia after the Peace of Vienna (1815),

The second half of the 19th century also did not contribute anything of importance to the architectural face of Warsaw. Similarly, the Polish Republic of 1919–1939 had no cultural-historical achievements to point to in terms of architectural advance. Granted, in some parts the city has grown at a downright American pace, but the new suburban extensions generally consist only of ugly, predominantly functional buildings devoid of any particular cultural uniqueness or beauty. The city has now again come under German dominion, and this time it will not be a temporary interlude as in the time of the Saxon kings; this time is the start of an enduring German epoch. We Germans are and will remain aware of the obligation which the great achievements of the German past in this region place on us, particularly in the areas of urban development and architecture. Now, during the war, is certainly not the time for mighty architectural endeavors. But this obligation will be met in a big way after the war is over, as soon as the Führer has made the final decision regarding Warsaw's position and status in the German sphere of influence. German architects, following in the footsteps of their great predecessors, will then once again impress on Warsaw a German character.

1Cf. Dr. Grundmann's "Führer durch Warschau" [ = "Guide to Warsaw"], p. 8. ...back... 2Cf. Grundmann op. cit., p. 13. ..back...

*[Trans. note:] The Desden Zwinger is a palace forecourt created by Daniel Pöppelmann in

1711–1722 for Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony. It was destroyed in 1945, and extensively rebuilt after the War. ..back...

|