|

Economic Development in the District of Warsaw (Part 2)

3. The Significance of the Vistula River for the Warsaw Basin

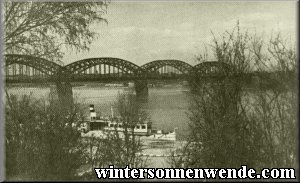

In the propaganda of the former Polish Republic, developing the Vistula was always a matter of great importance, as this river has long been called "the lifestream of Poland". One might therefore have assumed that during the two decades of their Republic's existence the Polish would have devoted constant attention to the development and care of their lifestream. But in fact this was not the case; for the state of the Vistula evidences next to no work at all in terms of stream improvement. To this very day the Vistula presents a desolate appearance even in the most important stretches of the General Government. Countless islands and sand banks lie every which way throughout the river and are a severe hindrance to any kind of river navigation. In the summer months depths of as little as 50 cm. are the rule, and depths greater than that are rare indeed.

This meager Vistula shipping volume is in complete contradiction to the boastful claims of Polish nationalists. There are several reasons for the utter neglect of the Vistula: One reason is the Polish inability to actively carry out any truly large-scale plans. Polish engineers did draw up gigantic plans for the improvement of the Vistula; indeed, there is perhaps no matter with respect to which as many plans of at times fantastic impracticability were drawn up in the former Republic of Poland as the improvement of the Vistula. But there is also no matter with respect to which as little was actually done.

But the main reason for the lack of attention paid to the needs of the Vistula can be found in the former Polish state's north–south orientation. The great coal transport artery from Kattowitz to Gotenhafen (Gdingen),* which corresponded to the nation's north–south orientation, seemed to the Polish authorities to be the most important traffic corridor. The degree to which this route was used ad absurdum by order of the Polish government is revealed by the almost unbelievable example that coal to be sent from Polish Upper Silesia to Vienna was first transported to the Baltic Sea via the Kattowitz–Gotenhafen corridor, then shipped by sea route to Trieste on the Adriatic, from where it was then finally sent on to Vienna by rail. There will be no more such nonsense. The coal corridor will certainly not lose its importance; it will continue to be used to ease traffic congestion on the Oder and will further be extended to accommodate traffic connections to the eastern part of the Baltic – traffic which shows a great potential for increasing. In this context the coal corridor even has an advantage over the Vistula, which is a much longer distance to travel due to its great eastward bend. However, this disadvantage of the Vistula for north–south traffic is at the same time an indicator of what the river is truly suited for: giving access to the East. That will require river amelioration measures to be taken along the entire Vistula. In the past century only the lower reaches of the Vistula passed through the Reich, while the remainder was first Austrian and then Russian or Polish. As a result of this political division of the river, no uniform stream control measures were taken. Only through the dictates of the Treaty of Versailles did the river become completely Polish up to the point where it entered the former Free City of Danzig; but the Poles never made use of this situation which would have been politically so advantageous for them. At long last, the Vistula, that fateful river in the East of the Reich, is in German hands from its source to its river mouth, and so all political barriers have fallen. The Vistula will no longer be treated like a proverbial stepchild. The work involved in regulating the Vistula will take years, as the river and its tributaries must be restructured from the ground up to meet the requirements of shipping and agricultural cultivation.

The northern part of the Vistula, extending from Warsaw to Bromberg [now Bydgoszcz] via Modlin and on to the Baltic Sea, will be of much greater significance. The conquest of the former Soviet Russian territory has resulted in the need to connect the Baltic with the Black Sea. It is best possible to do this via the Vistula and Bug and the canal connections of the Dnieper and Dniester rivers, which is why the Bug and the northern reaches of the Vistula must be developed. In this way a large part of the vast agricultural and raw materials resources of the East will be made available to the Reich and the entire European community.

Whether the great inland port of the East will turn out to be located within the old-established city itself or whether new port facilities will be constructed in its proximity downstream is irrelevant. In either case, the location of this mighty inland port of the future will quite naturally be in the Warsaw Basin, between the present city of Warsaw and the confluence of the Bug and the Vistula, since the Warsaw Basin occupies a key position with respect to the East. Plans are already being drawn up for such a port, which will be divided into a strictly industrial port and a trading port for cargo transshipping. This plan is but one part of the overall development and restructuring of the Vistula and Bug rivers.

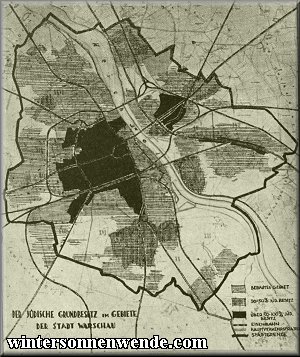

4. The Administration of Jewish-Owned Real Estate Of the many pressing economic problems facing the District of Warsaw, the exclusion of the Jews from the economy was of paramount importance; the Jews had established themselves so firmly in industry, trade and commerce that literally thousands of businesses were in Jewish hands. These businesses were soon rid of Jewish influence. Even some of the Poles have gratefully acknowledged the German administration's achievements in this respect. In particular, the Jews had secured for themselves a tremendous amount of real estate. The old Polish saying that "the Jews own the houses and the Poles only the streets" was the bitter truth. In fact, in the course of centuries and on the basis of a systematic settlement policy, the Jews had managed to bring one house after another into their economic grasp. The settlement pattern of the Jews was closely tied to their economic activity. They had always settled first in the city centers, from where they advanced into the surrounding, economically uniformly valuable regions. This pattern is evident in all the trading cities in the East. In Warsaw, the "Old Market Square" is the core around which the Jews have for centuries voluntarily created their own residential district, their Ghetto. It is the tragedy of this region that the reduction of German influence by means of the absorption of the Germans into the fabric of the eastern cities went hand in hand with the ever-increasing economic power of the Jews. German patrician houses and business firms were turned into centers of Jewish economic power. It is therefore nothing more than an act of historical justice that today, under German rule, the ill-gotten gains which the Jews have acquired – not as fighters and colonizers, but as parasites – are wrested from them again.

The Jews' inner attitude to their real estate acquisitions was the foremost deciding factor in this measure. If the Jews has been permitted to retain their right of disposal, their materialistic and speculative attitude would inevitably have induced them to try to retain their former influence on the economy in this way, and even to use their acquisitions to purposely sabotage the German measures for social recovery. The Jews were perfectly aware of the power they could exert over their masses of tenants and also over the workers in their employ. The shortage of housing was regarded by the Jews as a welcome opportunity for wild speculation, and the exploitation of the hardships of others brought easy profits without work and without effort. The Jews are not interested so much in a modest but secure capital investment as in the deliberate exploitation of their resources; the care and maintenance of their buildings was a practice barely known to them. The German administration thus saw itself faced with the task of taking the entire Jewish real estate, in the city as well as in the rural areas, into its own management. For the city of Warsaw this meant the setting up of an organization which would administer land and property holdings with a value amounting to approximately two-thirds of the city total. Due to the shortage of staff the municipal administration itself was unable to assume this responsibility directly; instead, it had to create an "extension" of itself for the purpose. The requisite legal basis for this was provided by the confiscation order of January 24, 1940. Aside from those exceptions which, for special reasons, were assigned individual trustees, the whole of the Jewish real estate was placed in the care of a general fiduciary. For administrative purposes this general trustee has at his disposal the managerial framework of the "Temporary Administration of Confiscated Properties", which is intended to be the organizational preliminary to a future real estate administration company. The systematic stocktaking of Jewish land and property holdings was begun in early June of 1940 and is presently complete. While some 4,000 properties were registered in Warsaw – among them some with hundreds of tenants –, the number of Jewish properties in the counties stands at well over 10,000. There are approximately 150,000 to 160,000 tenants to take care of. Figures such as these are beyond all reason. This enormous administrative responsibility demanded equal attention to details as to generalities. During the first year of administrative activity, necessarily restricted largely to organizational matters, a whole host of special problems were nevertheless encountered which were the inevitable consequence of the condition of the properties thus newly placed under the administration's care, and which demanded immediate attention. This double burden itself gave rise to considerable problems by no means easy to solve. Two problems were particularly urgent. For one, the extensive damage resulting from the war had to be repaired as far as possible. Part of the reconstruction of Warsaw was accomplished here almost without being accorded any notice at all. Central management ensured that this work was performed in the proper order, in accordance with the degree of urgency of each case. Many means which would otherwise have gone towards black-marketeering were put to use for the purposes of reconstruction, and the mortgaging of properties which in and of themselves could not raise sufficient funds to finance this work was a major budgetary factor in these projects. Improvements were frequently accompanied by an energetically promoted and fostered interior restoration of the buildings. A great part of the confiscated properties were, unfortunately, in economically very unsound condition. Maintenance obligations had been greatly neglected. The Administration was thus faced with many pressing short-notice repairs on top of the already costly restoration work on the one hand, and an inability to collect full rent on the other. War and savings losses have put many tenants in a position where they are unable to meet their financial obligations. Nevertheless, conditions have already improved greatly during the short time of German administration. This new administrative framework passed a major test in its handling of the great resettlement measures involved in the establishment of the Jews' Residential Quarter. In its function as collection and intermediary organization, it ensured the uninterrupted flow of public and private loan funds, thereby contributing to the minimization of those economic sacrifices which are part of any such endeavor. The administration of Jewish real estate lying within the boundaries of the Jewish Residential Quarter is carried out under German supervision which guarantees the value maintenance of these assets. The German property administration also has an important educational function. Hundreds of representatives and tenement superintendents are trained for their duties according to German standards. They are taught honesty and decency in business as well as the proper social attitude towards the tenant population. There is no more speculation and no more exploitation. The ideal which informs all actions and decisions is that this property under trustee administration represents great public wealth which needs and deserves the best of care. While the assignments given to the building trade create jobs and a living for those concerned, they do depend on ability and integrity in business relations. This attempt at training and education is frequently not all that easy, as there are many bad habits to purge which had been so commonplace before that they became accepted as a matter of course. The Property Administration does not consider the fulfillment of its responsibilities an end in itself. The foremost goal is always to manage this property in such a way that it is able, in accordance with National Socialist economic principles, to completely meet its social and economic obligations to the public interest. In this respect, a great deal of beneficial work owes its accomplishment directly to the exclusion of the Jews from the real estate scene.

*[Trans. note:] Gotenhafen and Gdingen were both contemporaneous names for present-day Gdynia. ...back...

**[Trans. note:] Coal was refined by means of a hydrogenation process. The coal was ground up and then hydrogen was added under high pressure; this liquefied the coal and caused the separation of various byproducts, which were then refined into a number of oils and fuels. For example, 5 parts coal ultimately yielded 1 part gasoline as well as enough residual energy to power the refinery without any external input of fuel. – This refining process is still being used in South Africa today. ...back...

|