|

Administrative Reconstruction and Development in Warsaw District

1. The Situation in General when German Administration Took Over

In almost every instance, a government official acting as "County Councilor" was charged with the governmental direction of a Polish "county" immediately upon the capture of the respective county seat even when the neighboring regions were often not yet under German control. For example, the County Councilor of Skierniewice was already appointed in mid-September 1939, in other words at a time when the great Battle of the Bzura was still raging only 15 to 20 km. to the north. The western counties, as well as some of the District's eastern counties, had already been placed in the charge of County Councilors prior to the capture of the cities of Warsaw and Modlin. After the capture of Warsaw, and after the Russian troops had moved out of the District's eastern part which they had temporarily occupied and retreated behind the line dividing the respective spheres of interest, all counties had been properly assumed by the German civil administration. With the establishment of the General Government, the title of "County Councilor" was changed to that of "County Administrator".

The armed forces carried out the clean-up of the battlefields as well as other clearing operations. Vast quantities of military spoils were collected, and tens of thousands of prisoners were quartered in temporary POW camps in several towns. Streets and bridges had been blasted, and in part given makeshift repairs by the Wehrmacht. Railway connections were mostly cut off, as were postal and telegraph installations; watermains had been largely destroyed.

Thousands of refugees from Warsaw and from throughout the entire former Polish nation roamed the rural areas. The numbers of refugees were further increased by the people whom the ravages of war had left homeless. The utter panic that had taken over the populace resulted in a terrible state of confusion. Business was next to nonexistent; most stores were closed and there was no market activity. In their fear of looting and requisitioning, the frightened rural populace hid all their stores and supplies, even buried parts thereof, and initially showed no inclination whatsoever to sell food to the city inhabitants. Harvesting and the further working of the land was frequently neglected. Country estates and farms were without management and leadership. Of the farm hands that still remained, many refused to work. Famine was imminent; a few cities were already almost out of bread. The numbers of livestock had dwindled due to the war. The Polish military's rigorous requisitioning drives had resulted in a particularly drastic decrease in the stock of horses. For this reason, numerous agricultural establishments no longer had the horses needed for harvesting and working the land. The war had nearly exhausted the stores of hay and feed grain. For the Jews, who were present in overly large numbers in all cities and towns of consequence, these conditions of disorder offered undreamt-of opportunities for making money and haggling. There seems to have been not a single necessity of everyday life with which they did not try to drive hard bargains. The Jews in particular had participated to their advantage in the widespread looting that had occurred. In their avarice they even went so far as to sell well-water by the glass and bread by the slice to the Polish prisoners interned in prison camps. There was no methodical and intensive system of agriculture. Agricultural machinery, artificial fertilizer and high-quality seed had hardly ever been used, and harvests generally amounted to only half the yield that could have been attained under good management. Here too, the influence of the Jews was inordinately strong. Trade and commerce and the agricultural processing facilities were mainly in Jewish hands. In one city of 17,000 inhabitants, there were 375 stores; 271 of them were Jewish-owned. Almost without exception, the cities of the District manifested conditions of culture and sanitation which in no respect met with German expectations. There were neither inns nor hotels where one could have expected a German to put up with the fare or accommodations. Living quarters with sanitary installations were rare, and in many cases there was no water supply at all which would not have posed health hazards. Aside from the previously described conditions resulting from the war, the organizational system which the German administration took over was equally inadequate from a purely structural point of view, and utterly insufficient for any kind of development of the country. In many areas the fundamental principle was that everyone could do whatever he wanted and leave the rest. There was no large-scale, foresightful planning. The Polish county administrators had seen to the regular routine administrative matters, but had shown no active initiative. The unsystematic way of operating may be seen, for example, in the way in which the construction of a hospital – a project requiring funds in the millions of zloty – had been begun with resources from current budgetary funds, without any financial reserves having been built up first. The result was that construction could always only proceed at such a rate as the current tax income permitted. Added to this was the fact that the Polish administration, even the local governors and village mayors, had ceased to fulfill their duties. The leading officials had fled weeks ago and taken with them important documents as well as the entire monetary funds. Some of the official buildings had been damaged in the war, others had been ransacked and looted, the safes broken into and plundered. Furnishings had frequently been destroyed or carried off. Police forces were nonexistent. In a few places, a Polish militia under the leadership of a self-appointed commander worked to preserve order, but their activities were largely for the benefit of their own pockets. Under these conditions, it was of paramount importance to set up an efficient administrative system as quickly as possible in order to free the country from this chaos. The small number of Germans who were entrusted with this task under those difficult conditions had to give their utmost in energy, self-sacrifice and willingness to take responsibility in order to master their assignment.

2. Reconstruction of Government Administration in Warsaw District Even before the Polish Campaign was concluded, the Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, in his capacity as executive power of the occupied Polish territories, had authorized the heads of the civil administration of the various Army Commands to appoint County Administrators to the former Polish counties. These Administrators were assisted by "administrative squads" consisting of 4 to 5 soldiers with 2 motor vehicles. The County Administrator was further assigned an official of middle rank as well as a county agriculturalist to serve as authority in his field. These administrative squads moved into sometimes still-burning county seats, close on the heels of the fighting troops. Their task was to restore the completely demolished administrative apparatus to working order. When the General Government was established on October 12, 1939 by order of the Führer, and the Governor-General had assumed office on October 26, 1939, the question became one of reconstructing the administrative system from the ground up. This was done according to the fundamentals of the leadership principle. The head of the General Government is the Governor-General, who is directly answerable to the Führer. To ensure consistent leadership and management of all organizational branches, he avails himself of the General Government's administrative authority, which provides administrative guidelines for the districts and is headed by the State Secretary. The head of each individual district is a Governor who sees to the entire administration of his district on behalf of the Governor-General. In the District of Warsaw, SA Major General Dr. Fischer assumed leadership of the District on October 30, 1939 in the capacity of District Chief. He has been Governor of the District ever since. The Chief of Administration1 as well as the Chief of the SS and Police2 are directly answerable to the Governor. The duties assigned to the District of Warsaw were initially dealt with by only a small staff, which jointly tackled all responsibilities as they came up. In time, the organizational system was configured into Departments and Divisions. Now that the administrative framework has taken on its final form, the District's administration is divided into 5 Departments assigned to the Chief of Administration, namely

Personnel Department, Department for Environmental Planning, Department for Price Control, Central Archives, and 10 Divisions, namely

Revenue, Justice, Economics, Food and Agriculture, Forestry, Labor, Propaganda, Research and Education, Building and Construction.

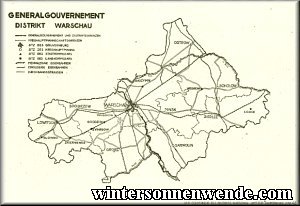

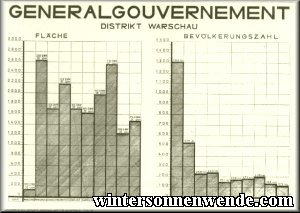

In the Polish Republic, the present-day territory of the District of Warsaw had been divided into 14 "starostys" corresponding roughly to German counties. In the interests of rendering administration as tight as possible, several of these previous territories have been combined in the course of reorganization. Aside from the city of Warsaw, 10 counties were initially set up which were later redesignated "county precincts". These are:

Garwolin, Siedlce, Sochaczew, Grojec, Ostrow, Sokolow, Lowitsch, Skierniewice, Minsk. The county precincts of Skierniewice and Lowitsch were later amalgamated for purposes of administrative simplification. Lowitsch is the county seat of this new precinct. Thus, the District of Warsaw presently consists of 9 county precincts and the city precinct of Warsaw. The county precincts are named for their respective county seats. The population of the precincts ranges from 100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants.3 The Office of County Administrator consists of the following Departments:

Department of Food and Agriculture, Education. Added to these are affiliated offices:

Inspection of Land, Inspection of Water Economy [ie. supply and distribution], Employment Center, Forestry Supervision, Inspection of Electrical Works. For purposes of the more efficient execution of their functions, these authorities are equipped to service more than one county precinct and are thus each affiliated with several County Administrators simultaneously. In several county precincts, Rural and City Commissioners serve as administrative branch functionaries of the County Administrator. Whereas the City Commissioners have immediate government control over the city administrations entrusted to them, the Rural Commissioners are charged with the jurisdictional supervision and policing functions of their rural districts. City Commissioners are appointed to the cities of Siedlce, Pruszkow and Lowitsch, and Rural Commissioners serve in

Subordinate to the County Administrator are Polish service functions which are kept under constant supervision by the county precinct department relevant to their field. Such service functions include:

the county veterinarian, the department for stockbreeding, the department for water economy, the taxation authorities, the head forestry offices. Further, the County Administrator is Chief of the District Council Administration. He is thus in charge of the county's various local and community institutions, namely:

the community hospitals, the community Health Care Centers, the local and community agricultural schools, the veterinary hospitals, the retirement homes, and miscellaneous other institutions. The county precinct Departments are run with relatively few German personnel. There is nothing even remotely like the degree of staffing exhibited by comparable service departments in the Reich. Considerable numbers of Poles and occasionally Ukrainians must therefore be called in so that all the work can be managed. The German role at this level of administration is increasingly restricted to the provision of leadership and supervision, and leaves other responsibilities to Polish officials wherever possible. That matters of predominantly German interest are handled exclusively by Germans, however, goes without saying. The administration of the county precincts in particular has been marked from the beginning by creative initiative and great decisiveness on the part of the individuals invested with these offices.

3. Reconstruction and Development of Community Administration When the Germans assumed administrative responsibility, Polish communities to a very large extent retained their previous levels of autonomy. Even today, Polish mayors generally still bear full and sole responsibility for the administration of their communities. In accordance with the former Polish regulations, the county precincts contain within their boundaries considerable numbers of so-called collective communities under the direction of bailiffs ("Wojts"). These collective communities consist of individual villages, headed by village mayors ("Soltys"). In the cities and county boroughs of a county, the Polish community leader has the title of mayor. Incidentally, the Polish term for mayor, "Burmistrz", shows that this word was adopted from the German ("Bürgermeister"); German administrative institutions in general have been of especially great significance in Poland for centuries. For example, the Polish word "Wojt" originated with the German word "Vogt",* and similarly, the Polish term for a village mayor, "Soltys", comes from the German "Schulze". In the majority of cases, the County Administrators have retained the Polish bailiffs and mayors in the interest of a smooth continuation of official matters. Ethnic Germans were invested as mayors or Wojts only in communities of whose population Germans constituted considerable proportions. During the organizational consolidation of the county precincts, the community administrative framework was also developed further. As in Polish times, everyday administrative matters are the province of the community secretary. The mayor is further assisted in matters of food supply and nutrition, as well as in the collection of agricultural products, by a specialist for food and nutrition. Community agronomists foster and promote agricultural production in the various communities. In several county precincts, regional physicians and veterinarians are assigned to 2 or 3 communities each. Such medical personnel is paid out of community funds and is responsible for matters of health care and disease control. The veterinarians are also called in for the inspection of the livestock quotas as these are turned in. The degree of autonomy granted the Polish communities by the Governor-General is in keeping with the guidelines according to which the General Government is to be an institution which the Poles can regard as their own. To date, experience has shown that despite the severe financial losses they have suffered, the war damage they have sustained, and the poor economic conditions that have resulted from the war, the Polish communities are by no means unable to survive – provided that they are placed under appropriately strict German supervision. On the whole, the Polish bailiffs and mayors have proven to be reliable. They are willing to render loyal assistance, even if they occasionally do have a hard time with rebellious elements in their communities.

1From October 26, 1939 to December 31, 1940, the office of Chief of Administration was held by Reichsamtsleiter Barth, who was recalled to Munich to the NSDAP's Department of Justice. As of January 1, 1941, Reichshauptstellenleiter Dr. Hummel has been Chief of Administration. ...back... 2From November 9, 1939 to July 22, 1941, the Chief of the SS and Police was SS Major General Moder who, as member of the Waffen-SS, was killed in action during the Russian Campaign. His position was then filled by SS Colonel Wigand, who joined the Waffen-SS on May 1, 1942. Since then, SS Colonel Dr. von Sammern-Frankenegg has been Chief of the SS and Police in the District. ...back... 3Cf. the map of the District of Warsaw. ...back...

*[Scriptorium notes:

the same linguistic root is evident in the name of the late Pope John Paul II, who was born Karol Jozef Wojtyla. So it seems not unlikely that the Polish Pope was of German

ancestry – especially since his mother's maiden surname was

Scholz – and that his name was a Polish version of "Karl Josef Vogt".] ...back...

|