|

Germany's 1923

Hyperinflation: A "Private" Affair

Article from The Barnes Review, July-Aug. 1999,

pp. 61-67.

Lagging behind other European nations, Germany had no central government until the formation of the German Federation in 1815. The major "German" finance houses of the medieval period had been quick students of Italian finance methods at Venice's Foundacio De Tedeschi, and some, like the Fuggers of southern Germany, had grown to international prominence as factors in financing the election of emperors. In 1900 the Deutsche Bank financed construction of the Turkey-Baghdad Railway. This meant German industry, already linked to Istanbul (the famous Orient Express line), could be directly linked to farther eastern markets, circumventing Britain's naval supremacy. Hjalmar Schacht, one of 20th-century Germany's key financial figures, noted that this railway disturbed England's rulers. There are other reports of British concern over German dynamism. Francis Neilson, a former British member of Parliament and author of The Makers of War, presented the viewpoint that England's "old boy network" didn't consider itself up to competing with Germany industrially. In 1907 the widely respected American diplomat Henry White was instructed to ascertain British views. He met with his friend Arthur Balfour. White's daughter "overheard" one of White's conversations with Balfour as follows (it was probably White's way of not directly violating secrecy pledges):

White: If you wish to compete with German trade, work harder. Balfour: That would mean lowering our standard of living. Perhaps it would be simpler for us to have a war... Is it a question of right or wrong? Maybe it is just a question of keeping our supremacy.1 European heads of state were still largely hereditarily selected. Court intrigue and the system of secret treaties played a larger role than today, and lent itself to warmongering. According to Neilson, the British Parliament had not been informed that England was committed to a continental war to defend France, if necessary.2 Adding to the problem, the Schlieffen Plan for the emergency military mobilization of Germany did not have the foresight to allow time for diplomatic negotiations. Thus the assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo by anarchists was given the power of a trigger in starting World War I. Alfred E. Zimmern's rare 13-page monograph, The Economic Weapon,3 written during World War I, deserves attention because of its content and its source. According to Prof. Carroll Quigley [himself a notable member of the Establishment; -Ed.], Zimmern was a member of what he called the "Anglo-American Establishment."4 Zimmern sums up the situation on page 1:

Zimmern pointed out this was the first time in history that such a large "siege" had been attempted, and Germany didn't think it was possible. "In December 1915, the chancellor remarked: 'Does anyone seriously believe that we can lose the war on account of a shortage of rubber?' Germany's war preparations were made on an estimate 'of a war of one year's duration at the outside.'" Then Zimmern raised the veil on what was planned for Germany:

The whole civilized world will be faced... with the prospect of a shortage, if not a famine over a period calculated... at no less than three years. And: "Some will have to go short. Who more naturally than Germany? It is not as if the boycott had to be organized. It will come about almost of itself unless special provision is made in the peace." But Lord Lothian (who Quigley lists as a fellow member with Zimmern of the Anglo-American Establishment), was the co-author of the Treaty of Versailles.5 The treaty would provide for the opposite of a just peace. The Treaty of Versailles turned out to be an instrument of continuing aggression. Even at the time, it drew strong condemnation. The American Secretary of State Robert Lansing wrote:

Lansing noted that:

Francisco Nitti, the prime minister of Italy, wrote:

The cost of the war of all participants totaled three times the value of all property in Germany. She was ordered to pay an impossible 1.7 billion marks a year (in foreign exchange) for 59 years, until 1988. Even worse, according to the normally circumspect banker, Hjalmar Schacht:: "The Treaty of Versailles is a model of ingenious measures for the economic destruction of Germany," adding:

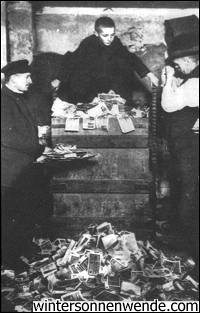

Further complicating matters, immediately after the surrender, on November 9, 1918, the threatened leftist and communist coup was carried out, when the Revolutionary Council of Commissioners of the People overthrew the German government and temporarily took power. England had financed 20 percent of World War I through taxation, France zero percent and Germany 6 percent. Schacht wrote that Germany's money supply rose from 7.2 billion marks in December 1914, up to 28.4 billion marks on November 7, 1918; the end of the open warfare. This meant circulation went from 110 to 430 marks per person. An index of wholesale prices had risen from 100 in 1913, to 234 in late 1918, performing close to British indexes. The effect on working people was cushioned as workmen's wages rose from 100 to 248 during the period. Thus World War I seriously damaged but didn't destroy Germany's monetary system. That came under the auspices of the occupying forces. The great German hyperinflation of 1922-23 is one of the most widely cited examples by those who insist that private bankers, not governments, should control the money system. What is practically unknown about that sordid affair is that it occurred under control of a privately owned and controlled central bank. The Reichsbank had a form of private ownership, but with public control; the president and directors being officials of the German government, appointed by the emperor, for life. There was a sharing of the revenue of the central bank between the private shareholders and the government. Unfortunately, the League of Nations experts delegated to guide the economic recovery of Germany wanted a more free market orientation for the German central bank.9 Schacht relates how the Allies had insisted that the Reichsbank be made more independent from the government: "On May 26, 1922, the law establishing the independence of the Reichsbank and withdrawing from the chancellor of the Reich any influence on the conduct of the bank's business was promulgated."10 This granting of total private control over the German currency set the stage for the worst inflation of all time. How does the value of a currency get destroyed? In a sentence, by issuing or creating tremendously excessive amounts of it. Not just too much of it, but way too much. This excessive issue can happen in different ways; for example, by British counterfeiting, as occurred with the U.S. continental currency. The central bank itself might print too much currency; or the central bank might allow speculators to destroy a currency, through excessive short selling of it, similar to short selling a company's shares. The destruction of a national currency through "speculation" is what concerns us in this case. It is also a timely topic considering how speculation was recently allowed to destroy several Asian currencies, which have dropped over 50 percent against the dollar, in a few months time, threatening the lives of millions. It works like this. First, for whatever reason, there is some obvious weakness involved in the currency. In Germany's case it was World War I, and the need for foreign currency for reparations payments. In the case of the Asian countries, they had a need for dollars in order to repay foreign debts coming due. Such problems can be solved over time and usually require some national contribution toward their solution, in the form of taxes, or temporary lowering of living standards. However, because currency speculation is still erroneously viewed as a legitimate activity, private speculators are allowed to make a weak situation immeasurably worse; to take billions of dollars in "profits" out of the situation, by selling short the currency in question. Not just selling currency which they owned, but making contracts to sell currency which they didn't own - to sell it short. If done in large enough amounts, such short selling soon has self-fulfilling results, driving down the value of the currency, faster and further than it otherwise would have fallen. Then at some point, panic strikes, which causes widespread flight from the currency by those who actually hold it. It drops precipitously. The short selling speculators are then able to buy back the currency which they sold short, and obtain tremendous profits, at the expense of the industrialists and working people whose lives and enterprises were dependent on that currency. The free market gang claim that it's all the fault of the government that the currency was weak in the first place. But by what logic does it follow that speculators take this money from those already in trouble? And they call this business? It should be viewed as a form of aggression, no less harmful than dropping bombs on the country in question. The recent outrage expressed on this by the prime minister of Malaysia got it right. The proper reaction would be to help strengthen the currency, not promote its destruction. Industrialists should realize that when they allow such vicious activity to be included under the umbrella of "business activity," they are cutting their own throats. They should help isolate such sociopathic speculators, so that they can be stopped by the law. Back to Germany. Far too many German marks were being created under the privately controlled Reichsbank. Exactly how, will be discussed shortly. These excessive issues drove down the value of the mark: By July 1922, the German mark fell to 300 marks for $1; in November it was at 9,000 to $1; by January 1923 it was at 49,000 to $1; by July 1923, it was at 1,100,000 to $1. It reached 2.5 trillion marks to $1 in mid-November 1923, varying from city to city.11 In the monetary chaos, Hamburg, Bremen and Kiel established private banks to issue money backed by gold and foreign exchange. The private Reichsbank printing presses had been unable to keep up, and other private parties were given the authority to issue money. Schacht estimated that about half the money in circulation was private money from other than Reichsbank sources. Hjalmar Schacht's 1967 book, The Magic of Money, presents what appears to be a contradictory explanation of the private Reichsbank's role in the inflation disaster. First in the hackneyed tradition of economists, he is prepared to let the private Reichsbank off the hook very easily, and blame the government's difficult situation instead, and minimized the connection of the private control of the central bank with the inflation, as mere coincidence:

Schacht lamented:

In other words, they did it to save the government; assumedly making the new issues of Reichsmarks available for government expenditures. After a few pages, Schacht gave the real explanation. Schacht was a lifelong member of the banking fraternity, reaching its highest levels. He may have felt compelled to give his banker peers and their PR corps something innocuous to quote. But Schacht also had a streak of German nationalism, and more than that, an almost sacred devotion to a stable mark. He had watched helplessly as the hyperinflation destroyed "his mark." For whatever reasons, after 44 years he then proceeded to let the cat out of the bag, writing in German, with some truly remarkable admissions that shatter the "accepted wisdom" the financial community has promulgated on the German hyperinflation. But first, some background to the events of 1923 is needed: As the hyperinflation wreaked destruction many plans were put forward to stabilize the currency. In 1923, a conservative monetary theorist, Karl Helfferich, advanced a plan of basing the currency on agricultural grains and putting its administration into the hands of a private bank run by agricultural interests. The support of the farming community was not sufficient to have this plan adopted. Because the mark had been so badly ruined for 18 months, it was felt that, psychologically, an altogether different currency was necessary. Plans centered on a new currency to be called the Rentenmark. The plan was simple: introduce the new currency, in a limited quantity and don't overissue it, so that the notes keep their value and thereby reestablish confidence. In order to create a largely psychological separation from the Reichsbank, the Rentenbank was set up to loan Rentenmarks, to the Reichsbank; and the Reichsbank issued Rentenmark credits. The Rentenbank was not truly independent of the Reichsbank. Schacht, with 23 years of banking experience, agreed to be made the government's commissioner of currency, a new position created to stabilize the currency. At the time, monetary theorists such as Helfferich were arguing that the state wasn't powerful enough to "create money which would command public confidence, and that only the business elements of the country acting of their own free will were competent to accomplish this task."13 Schacht knew better. This process took time, to convince the population that the new currency would not be over-issued: "The invention of the Rentenmark did not stabilize the mark. The battle for stabilization continued for a year, passing through many a difficult phase," he wrote, asserting that it was not the Rentenmark but the subsequent credit restrictions on how many were created that stabilized the currency.14 The formal structure of the Reichsbank had apparently not been altered in this stabilization period; but it was clearly the government and society that now actively exercised the monetary control:

The Rentenmarks were put into circulation in three days, from November 15, 1923. They were not legal tender; there was no fixed relation to the fallen Reichsmark; and the Rentenmarks could not be used for international payments. Schacht stopped all other money issuers and sent all Reichsbank holdings of private money back to their source for immediate payment, despite great howls of pain from all these private moneyers; such as the Hugo Stinnes group. The Rentenmarks were expressly forbidden to be transferred to foreigners. This meant that speculators could not trade them for foreign exchange to support their speculations when prices went against them. Schacht's initial actions thus crushed the speculators, a necessary first step in most monetary reform:

How did Schacht determine the value of the Rentenmarks? By the seat of his pants. On November 20, 1923, it was set at $1=4.2 trillion Rentenmarks. Fixing it there was convenient because in peacetime it had been $1 to 4.2 marks. He remarked that:

It was in describing his 1924 battles in stabilizing the Rentenmarks that Schacht made his revelation; giving the real mechanism of the hyperinflation. Schacht was obviously very upset when the speculators continued to attack the new Rentenmark currency. By the end of November 1923:

Now however, three things had happened. The emergency money had lost its value. It was no longer possible to exchange it for Reichsmarks. The loans formerly easily obtained from the Reichsbank were no longer granted, and the Rentenmark could not be used abroad. For these reasons the speculators were unable to pay for the dollars they had bought when payment became due (and they) made considerable losses.18 Thus Schacht is telling us that the speculation against the mark, the short selling of the mark, was financed by lavish loans from the private Reichsbank. The margin requirements which the anti-mark speculators needed, and without which they could not have attacked the mark, was provided by the private Reichsbank. This contradicts Schacht's earlier explanation, for there is no way to interpret or justify "lavishly" loaning to anti-mark speculators as "helping to keep the government's head above the water." Just the opposite. Schacht was a bright fellow, and he wanted this point to be understood. He waited until he wrote The Magic of Money in 1967. His earlier book, The Stabilization of the Mark (1927), discussed inflation profiteering, but did not clearly identify the private Reichsbank itself as financing such speculation; making it so convenient to go short of the mark. Thus we now realize that it was a privately owned and privately controlled central bank, which made loans to private speculators, to enable them to put up the necessary margin to speculate against the nation's currency. Such speculation helped create a one-way street, down, for the German mark. Soon a continuous panic set in, and not just speculators, but everyone else had to do what they could to get out of their marks, further fueling the disaster. This factor has been largely unknown, and "the government" typically gets the blame for this mother of all inflations, in economic propagandizing. Why did Schacht give these details after 44 years, when he could have easily "forgotten" about them? Probably because his sense of justice was deeply offended over the destruction of the mark by Germany's plutocracy - especially her bankers. For hundreds of years Schacht's family lived in the Ditmarschen area, between the Elbe and Eider rivers. This is a land of free farmers, notably lacking the castles found in most parts of Germany. Schacht studied German philology, then did his doctorate on the English mercantilists, demonstrating how they were aware of the quantity aspect of money from the 1500s and 1600s.19 Finally, Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht was his full name; his father was a naturalized American citizen who had returned to Germany as a newspaper editor. In December 1923, Schacht was made president of the Reichsbank. Before assuming office, he went to England for a meeting with Montagu Norman, governor of the Bank of England. Schacht wrote:

Legitimate credit demands led to a rapid growth of credit extended by the Reichsbank and the Rentenbank from 609 million Rentenmarks at the end of 1923, to 2 billion at the end of March 1924. Sensing weakness, the speculators moved in for a kill, ignoring the law regarding foreign exchange purchases. In March of 1924 Schacht's regulations (he calls them "instructions") were being violated by the banks: "[W]hereby foreign exchange purchase orders were to be executed by the banks only if full cover in German currency was provided by the purchaser, this had not been heeded by various banking firms." These banks, including one of the largest, impudently ignored Reichsbank reminders, so their bills were denied re-discounting by the Reichsbank, effectively blocking them, and ending the violations. From April 7, 1924 the Reichsbank refused to issue new credits for two months. "The Reichsbank plumped for the stability of the mark," wrote Schacht. The speculators had to turn their foreign holdings over to pay their debts, as their trading positions against the Rentenmark lost money. In this way the Reichsbank increased its foreign exchange reserves from 600 million marks worth, at beginning of April 1924, to more than double that by August 7, 1924.21 This indicates a still immense amount of anti-mark speculation: "...[A]nd the country was still filled with numbers of such speculators, who were not in the least concerned as to whether their good name and reputation suffered so long as they could pocket the profits," wrote Schacht.22 The contraction pursued by Schacht was brutal. One-month money rates went from 30 percent to 45 percent. Overdraft charges rose from 40 percent to 80 percent! After July 1924 they began falling. Schacht's restriction of money was so harsh that the German government-operated post office and railways formed their own banks and began building capital much faster than the private sector. By the end of 1924, merchants and others were treating the Rentenmark and the old Reichsmark as equal, and Schacht converted the Rentenmarks into Reichsmarks. He had always been against the Rentenmarks, considering them a monetary error: "I made every endeavor to take the Rentenmark out of circulation as quickly as possible. To this end the Reichsbank gave the Rentenmark parity with the new Reichsmark" and converted them into Reichsmarks. In 1923 the League of Nations had invited Gen. Charles Gates Dawes to chair a committee to deal with the controversial problem of German reparations payments. The Dawes Report recommended reducing the reparations from 132 billion marks to 37 billion marks. America would lend Germany money for reparations payments to France and England, which countries would then be able to pay some of their war debts. Dawes was a banker and owned the Central Republic Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago. The Allies implemented the plan; Dawes shared the Nobel Peace Prize for 1925 with Austen Chamberlain and then became vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929, under Calvin Coolidge. In 1932 Dawes became chairman of Hoover's depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corp., but then Dawes's bank failed and became the largest loss of the Reconstruction Finance Corp., costing the U.S. taxpayers $90 million.

Later in 1924 there was a Dawes Plan loan to the Reichsbank, after which foreign credits began to pour in. Foreign bankers had confidence in Schacht. He was against the loans, and insisted that any foreign borrowings only be to finance production, not luxury, or consumption. This policy, from 1924 to 1929, resulted in Germany establishing Europe's most modern factory system of the period. In July 1925, laws were passed to go back and examine and adjust inflation transactions. Injured parties could receive up to 25 percent of the real value of property they had exchanged for the bad paper. Schacht would resign the Reichsbank presidency in 1930, in protest over some economic rulings of the Allies. He was later reappointed when the National Socialists came to power. When the war ended, a destitute Adolf Hitler was given an assignment by German army intelligence: to watch a tiny political group called the German Workers Party. He attended a small meeting where the ideas of Gottfried Feder made a deep impression on him. In Mein Kampf Hitler wrote:

Feder's captivating ideas were about money. At the base of his monetary views was the idea that the state should create and control its money supply through a nationalized central bank rather than have it created by privately owned banks, to whom interest would have to be paid. From this view was derived the conclusion that finance had enslaved the population, by usurping the nation's control of money. Feder's monetary theories could easily have originated from the work of German monetary theorists such as George Knapp, whose book The State Theory of Money (1905) is still one of the classics in the monetary area. Right on page one, Knapp nails it:

Knapp describes the invention of fiat money in these terms: "the most important achievement of economic civilization." For Knapp, the determination of whether something was money or not was: "our test, that the money is accepted in payments made to the state [i.e., government] offices."24 Near the end of that book, Knapp casually mentions how German monetary theorists of his day, and earlier, would study and discuss American monetary theories. Thus the ultimate source of Feder's viewpoint was probably the American Populist movement of the 1870s and the ideas that movement promoted to establish a permanent greenback system. When the National Socialists came to power, Schacht was reappointed head of the Reichsbank, partly to reassure German big business and foreign bankers. Schacht ridiculed Feder's monetary views:

Konrad Heiden noted that:

Feder's faction was then given the four-year plan, to keep them busy.26 Feder quickly lost the battle with Schacht and the German business establishment. Perhaps he was in over his head monetarily. He wrote of his monetary plan: "Intensive study is required to master the details of this problem... a pamphlet on the subject will shortly appear, which will give our members a full explanation of this most important task..."27 But this was 1934, which means he hadn't clearly reduced the problem to written form since 1919, over 15 years. "When the time comes, we shall deal with these things in further detail..." Feder wrote, but indeed his party was in power, and the time had come. Feder was put out to pasture by the National Socialists, serving as an under secretary in the Ministry of Economic Affairs, later to be transferred to commissioner for land settlement and then completely sidetracked as a lecturer at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. Hitler and the National Socialists came to power on January 30, 1933. Germany's foreign exchange and gold reserves had dropped from 2.6 billion marks in late 1929, down to 409 million in late 1933 and to only 83 million in late 1934.28 According to classical economic theory, Germany was broke and would have to borrow. But classical economic theory is not very accurate.

Notes:

1Allan Nevins,

Henry White, Thirty Years of American Diplomacy. New York: Harper

Bros.,

1930, pp. 257-58. ...back...

2Francis Nielsen, The Makers of

War, Appleton, Wisconsin: Nelson Publishing Co., 1950. ...back...

3A. E. Zimmern, The Economic

Weapon. New York: George

Doran, 1913-17. ...back...

4Prof. Carroll Quigley, The

Anglo-American Establishment. New York: Books in Focus, 1982. ...back...

5Konrad Heiden, Der

Fuehrer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1944 (written 1934),

pp. 639-49. ...back...

6Robert Lansing, The Peace

Negotiations. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1921,

pp. 272-75. ...back...

7Francisco Nitti, The Wreck of

Europe. As quoted by Nielsen, op.cit. (Note 2), p. 151. ...back...

8Hjalmar Schacht, Stabilizing

the Mark. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1927,

pp. 46-51. ...back...

9ibid., pp. 116-7. ...back...

10ibid., p. 50. ...back...

11ibid., pp. 50-51. ...back...

12Hjalmar Schacht, The Magic

of Money. London: Oldbourne, 1967. Trans. by P. Erskine;

pp. 65-6. ...back...

13Schacht, op.cit. (Note 8),

p. 84. ...back...

14Schacht, op.cit. (Note

12), p. 68. ...back...

15Schacht, op.cit. (Note 8),

p. 89. ...back...

16ibid., p. 112. ...back...

17ibid., p. 102. ...back...

18Schacht, op.cit. (Note

12), p. 70. ...back...

19Norbert Muhlen,

Schacht - Hitler's Magician. New York: Alliance/Longmans Green Co.,

1939. Trans. by E. W. Dickes. ...back...

20Schacht, op.cit. (Note 8),

p. 208. ...back...

21Schacht, op.cit. (Note

12), p. 72. ...back...

22Schacht, op.cit. (Note 8),

p. 159. ...back...

23As quoted in Hitler's Official

Program by Gottfried Feder. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1934; New

York: Howard Ferbig Press, 1971, p. 56. ...back...

24George Knapp, State Theory

of Money. 1909. London: Macmillan, 1924,

pp. 92-95. ...back...

25Schacht, op.cit. (Note

12), p. 49. ...back...

26Heiden, op.cit. (Note 5),

p. 480. ...back...

27Feder, op.cit. (Note 23),

pp. 59, 92. ...back...

28Stephen M. Roberts, The

House That Hitler Built. New York: Harper Bros., 1938,

pp. 146-47. ...back...

Germany's 1923 Hyperinflation A "Private" Affair |