|

Holocaust at Dresden

Article from The Barnes Review, February 1995, pp. 3-13.

After nearly three years of unremitting Allied air offensives against Germany's civilian population, plans for the destruction of the open city of Dresden, incinerating at least 135,000 people, took shape on March 30, 1942. However the seeds of such inhuman hate had long since found fertile soil at 10 Downing Street and within the White House. On the above date Prof. F. A. Lindemann, later, Lord Cherwell, the Prime Minister's Science Advisor and a Jewish refugee from Germany, delivered to Winston Churchill a fateful report. In his book Bomber Command Max Hastings stated that "Cherwell's Report provided the final rationalization for the program Bomber Command was undertaking, and it would henceforth be paper-clipped to the plans of the bomber offensive."

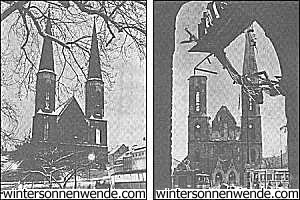

There were of course discussions and disagreements regarding strategic and tactical approaches to the bombing of Germany. But Lindemann's report is considered the basic text behind the wholesale bombing of civilian targets. Prior to the report's dispatch to Churchill, a February 14, 1942 Air Ministry directive to Bomber Command from Air Vice Marshal Sir Norman Bottomly contained the following Valentine's Day message: "You are accordingly authorized to employ your forces without restriction... [operations] should now be focused on the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular, of the industrial workers." On February 22, while Churchill was staying at the White House, it was decided that Air Marshal Arthur Harris would leave his post as head of the RAF delegation in Washington (an assignment he had held in neutral America beginning June 12, 1941) to head Bomber Command. This fateful reassignment would team Harris with a PM of kindred instincts in one of Western history's most costly and ghastly undertakings. The first chapters of World War II, from Germany's Sept. 3, 1939 invasion of Poland to the May-June 1940 clash in the West when France capitulated and Britain was driven from the continent, saw a scarcity of bombing by the belligerents. This was largely the period of "Sitzkrieg" and "Bore War" during which Germany's bombing of Warsaw prior to Poland's surrender marked the only major incident; a relatively moderate attack that proved costly to Germany on the propaganda front. Throughout the 1939-40 months of frontal stalemate in the West, Hitler didn't order the Luftwaffe to bomb Britain (while working continually for a negotiated peace with London that would allow him to concentrate on his plan for land acquisition in the East and the destruction of Bolshevism's Soviet bastion). The Royal Air Force confined its activities to the dropping of propaganda leaflets. The bombing of the open city of Freiburg-im-Breisgau on May 10, 1940, killed 22 children, 13 women, 11 men and 11 soldiers. Whether the bombers were French, British or even German has never been determined but the civilians killed and the property destroyed were real and gave Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels grist to promise that the Luftwaffe would answer the destruction "in a like manner." Four days later the Germans bombed Rotterdam. From northern German airfields some 100 Heinkel III bombers were poised to attack remaining resistance zones in the city. However, surrender negotiations with the Dutch government were in progress. The raid, planned for 1500 hrs. (3 pm), was ordered postponed after takeoff on a flight of about 100 minutes to target areas. The Dutch government had been stalling during negotiating sessions. German terms were finally agreed to five minutes before the time set for the attack. But the recall could not be signaled to those bombers that had crossed the Netherlands border. At that point they had reeled in their trailing aerials allowing long range reception. A swift fighter was dispatched to head off the bombers, and from a German panzer position on the ground at Rotterdam, where the mission-scrub signal had been received, signal flares were fired to ward off an attack that began just as the flares went up. The signal was received in time to disengage 40 of the Heinkels. The city's main water supply system was hit, and considerable fire ensued in one area (no incendiaries were dropped) due largely to hits on a margarine plant from which streams of burning oil flowed. In 1962 the Rotterdam government released figures showing that 980 people had been killed in the raid. The considerable devastation in the city gave Allied propagandists a field day, and Rotterdam became the greatest war atrocity story since Japan's "Rape of Nanking" in the 1930s. In his 1963 book The Destruction of Dresden David Irving noted that "Ninety four tons of bombs had been dropped... By comparison, close to 9,000 tons of high explosives and incendiaries were dropped on the inland Ruhr port of Duisburg during the triple blow of 14th October 1944." With Germany's bombing of Britain following France's surrender, strategic targets were singled out and hit with a high degree of accuracy. But on the night of August 24, 1940 (the main London targets being the vital East End dock-shipping-industrial areas), the target was the oil storage depot at Thames Haven. A navigational error led to the bombing of parts of the East End, the City and St. Giles. The bombing of central London drew the immediate retaliatory response of the Royal Air Force. The following night it bombed Berlin, with slight effect. This enraged Hitler, who issued a command that may have cost Germany victory. He ordered that the Luftwaffe switch its attacks to London and away from RAF installations and radar sites. This allowed the severely depleted Fighter Command a short but much-needed period to regroup. The Luftwaffe's incredibly costly (most particularly in terms of seasoned pilots and crew) London "Blitz" is dated from September 7, 1940 to May 16, 1941. Luftwaffe figures show that throughout this period 35,177 tons of bombs were dropped during 71 major attacks on London and other areas of industrial concentration, such as Hull, Liverpool and Manchester. The British calculated that, by the end of 1940, 13,339 Britons had been killed in raids. The German raid ranking with Rotterdam in terms of propaganda value was the bombing of Coventry in November, 1940. In bombing this industrial city Coventry's Cathedral was nearly demolished. Pictures of its ruins filled America's newspapers and newsreel screens. In his 1975 book The First Casualty (the title evidently taken from U.S. Sen. Hiram Johnson's 1917 observation that "The first casualty, when war comes, is truth."), Philip Knightly noted that the London Times editorialized on the "butchery at Coventry... The wanton slaughter by a people pretending to be civilized who, it would seem, kill mostly for the joy of destroying." Of this Knightly wrote: "Coventry was actually a legitimate military target, one of the keys to the British war effort" containing such plants as the Standard Motor Co., the British Piston Ring Co., the Daimler motor works and Alvis aero-engine factory. The British had known of Germany's intent to bomb Coventry due to an early intercept of Germany's Enigma code system by way of its Ultra codebreaking device. But Churchill vetoed interception of the Luftwaffe attack for fear that it would tip the Germans to the fact that their main code had been broken. Thus Coventry entailed a double deception on the part of the British. But this did not deter Churchill from ordering "Operation Rachel." This was the codename for the December 12, 1940 Bomber Command attack on Mannheim. On the PM's direct order it was to be a reprisal for the considerable damage done to Coventry and the first occasion in the relatively brief annals of air warfare that an entire city was to be the deliberate target of attack. Britain had begun the war with a somewhat antiquated bomber capacity. But by 1942 and with America's full material support, Bomber Command was a formidable force. In the spring of 1942 Harris sold Churchill and Chief of Air Staff Sir Charles Portal on a 1,000-plane raid. Stretching all human and material resources, 1,047 planes, largely with inexperienced crews, were gathered. When Churchill and Harris discussed potential casualties, the PM said he was prepared for the loss of 100 planes. Hamburg, Germany's second largest city, was to be the target. But weather conditions dictated a switch to the secondary target and Germany's third largest city, Cologne. The raid was carried out May 30 and it was a success. The city along the Rhine burned deep red well into the sky, the great Cathedral's twin spires (one of which would subsequently be destroyed) clear silhouettes to the airmen above. The raid had wrought instant devastation unequaled since biblical lore. Over 12,000 structures had been totally or partially destroyed, with 45,000 people left homeless. Remarkably, only 496 dead were counted. The water, power, gas and telephone complexes were in shambles and 36 factories were destroyed, 70 more badly damaged. Bomber Command was delighted at the loss of only 40 aircraft. Max Hastings noted in Bomber Command that "It was a mere token of the destruction Bomber Command would achieve in 1942 and 1943..." In the latter months of 1942 U.S. Army Air Corps B-17s and B-26 Liberators began limited daylight operations against targets in France and Germany. The Air Corps' top brass under Gen. H.H. "Hap" Arnold, in conjunction with Bomber Command's leaders, were pushing for an all-out campaign of U.S.-daylight / RAF-night operations. The American airmen had an added incentive. They wanted the postwar establishment of a separate armed service co-equal with the Army and Navy. The bomber offensive was their prime opportunity to show what they could do, and it would lead to many an unnecessary but destructive mission. The efforts of the Air Corps Bomber Command lobbying were fully rewarded at the Roosevelt-Churchill Casablanca conference in January, 1943. A Casablanca directive read: "Your primary aim will be the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to the point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened..." Following Casablanca, America's bomber presence escalated markedly, with USAAF (U.S. Army Air Force) fields increasingly dotting the fields of eastern England. The stage was fully set for one of history's darkest dramas, and one that would place gold stars signifying a family member killed in action in the front windows of tens of thousands of American homes. The physical punch to achieve what "Bomber" Harris had envisioned was now in place. Max Hastings wrote: "Long before Casablanca, or even before Cologne, Harris had conceived his campaign for the systematic laying-waste of Germany's cities, and he never had the slightest intention of being deflected from it." In the summer of 1943 Bomber Command was to unleash its most lethal strike of the war save for Dresden, and it would provide the first major instance of British and American public doubt and criticism. Although Hamburg had "weathered" Harris's initial 1,000-plane raid, it would be visited in a manner that can only be recalled as a determined atrocity. In Bomber Harris author Dudley Saward states that the obliteration of Hamburg, "which went by the ominous code name of 'Gomorrah,' was planned to take place over a period of four nights." Before his crews took off on the first assault the night of July 24-25, Harris told them: "The Battle of Hamburg cannot be won in a single night. It is estimated that 10,000 tons of bombs will have to be dropped to complete the process of elimination. To achieve the maximum effect of air bombardment this city should be subjected to sustained attack. On the first attack a large number of incendiaries are to be carried in order to saturate the fire service." Few could misunderstand these words or the intent behind them. This was not a surgical or even carpet bombing strike against military or industrial targets. Clearly, this was the premeditated murder of a city and its people. In the series of four Hamburg raids, July 24 to August 3, Bomber Command dropped 8,621 tons of bombs on the city, 4,309 tons being incendiaries. Eighth Air Force B-17s dropped 771 tons of explosives during the third raid. Initial deaths were estimated at 41,800, but many thousands more died subsequently or were never counted due to incineration, burial beneath rubble or having been blown to bits. The four-raid total may have equaled Great Britain's official total losses for the war of 51,509. The Bomber Command Diaries, published in 1985 by Penguin Books, London, states that the August 2-3 raid largely failed due to thunderstorms. Thus most of the destruction was wrought in three raids. In The Destruction of Dresden Irving wrote that "When rescue teams finally cleared their way into hermetically sealed bunkers and shelters, after several weeks, the heat generated inside had been so intense that nothing remained of their occupants: only a soft undulating layer of gray ash was left in one bunker, from which the number of victims could only be estimated as 'between 250 and 300'..." Despite the highly restrictive censorship regulations applied to Allied war correspondents (already deemed supportive of the Allied cause as a condition of clearance) fairly large bits and pieces of what the bomber offense was about leaked to some prominent civilian figures. In England, among the most telling critics were the country's two premier military historians, Maj. Gen. J.F.C. Fuller and Captain Basil Liddell Hart. In August, 1943 Fuller drafted an article (evidently not published) to the London Evening Standard in which he stated: "The worst devastation of the Goths, Vandals, Huns, Seljuks and Mongols pales into insignificance when compared to the material and moral damage now wrought..." Following the thousand-plane Cologne raid Hart drafted a private "reflection" that observed: "It will be ironical if the defenders of civilization depend for victory upon the most barbaric, and unskilled, way of winning a war that the modem world has seen... We are now counting for victory on success in the way of degrading it to a new low level..." As stated in The Army Air Forces in World War II, plans were drawn up in early June, 1944 to define the post-D-Day invasion bomber campaign. The recommended priorities to both Bomber Command and the U.S. 8th and 15th Air Force (in Italy) were, in order of priority, oil production, jet and V-weapons, ball bearing plants and tank factories. As Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower left both the American commanders (Gens. Spaatz and Doolittle) and Harris free to develop independently their strategic bombing campaigns as they saw fit. It was clearly an opportunity to curtail Harris's incredible excesses. But Eisenhower, essentially a high political functionary in uniform, based higher decisions on the wishes of the President and the Prime Minister.

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, compiled after the war, concluded that deaths in

Darmstadt that night may have exceeded the RAF figures (taken from initial German figures) by

5,000 because all deaths were not reported by the 49,200 made homeless by the raid and

evacuated from the city. Today, the city of Darmstadt has final figures of 12,300 dead and

70,000 homeless.

. Part 2 The Infernal Firestorm - A Glimpse of Hell Thus a long pattern of operational intent, in which everything on German soil that stood, moved or breathed was considered a legitimate recipient of the bomb bay payloads, had been established long before it became Dresden's turn. To begin with, the city was not an industrial center of even moderate importance. It had been bombed once, some 20 USAAF planes hitting with considerable accuracy the city's small industrial area as a secondary target at midday on October 7, 1944 during an attack on the Ruhland oil refinery.

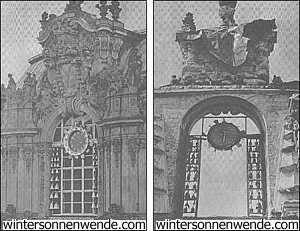

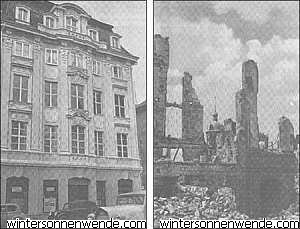

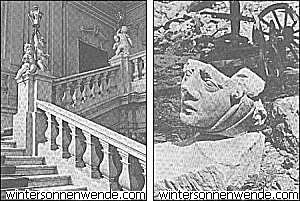

The essence of pre-holocaust Dresden was described in David Irving's book: "Not endowed with any one great capital industry like those of Essen and Hamburg, even though Dresden was of comparable size, the city's economy had been sustained in peacetime by its theaters, museums, cultural institutions and home industries." Irving noted that "for the British prisoners of war... life could not easily be bettered. The Dresdeners were familiar with the English from pre-war days, when the city had been a cultural center and many made friends among the prisoners - a large section of which were from 1st Airborne Division contingent captured at Arnhem." The factor of pre-war English familiarity with Dresden, generations of students having visited it on the Grand Tour, would play a major part in the raid's aftermath. Dresden's fate had been sealed at the February 4-11, 1945 FDR-Churchill-Stalin conference at Yalta. Reports about the Dresden decision center on Stalin's desire to see it savaged as a means of enhancing the Red Army's offensive by jamming up German troop movements. U.S. Chief of Staff George C. Marshall announced publicly that Dresden had been attacked at Stalin's specific request, although after the war the Soviets and East Germans repeatedly referred to the raid as a "diabolical plan" of Churchill's "to kill as many people as possible."

The concession was allegedly made to soothe the increasingly arrogant and intransigent Kremlin dictator. But given the fact that at Yalta Stalin achieved control over Eastern Europe, in-effect control of Mongolia, Japan's Kurile Islands, an occupation zone in Korea and a guarantee of $20 billion in eventual German reparations, one might have thought that the bear had been amply fed. After Yalta and the war, Churchill of course went into his "deeply suspicious of Stalin" act just as he had feigned surprise at FDR's unconditional surrender announcement at Casablanca. However, just before flying from Russia on February 14, at the very moment of Dresden's awesome trauma, he lauded his hosts' "great leader." And the ever theatrical PM, who certainly ranked with fellow dipsomaniac thespians John Barrymore and Richard Burton, lauded "The redeemed Crimea, cleansed by Russian valor from the foul taint of the Huns." Dresden had once been a pivotal communications and rail center important to the Wehrmacht. But as Irving notes, by the time it received its fatal blow, "The city's strategic significance was scarcely marginal..." It was home to 630,000 permanent residents, its numbers swelled by German and Allied wounded, Allied POWs and hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing areas in the path of the Red Army's advance. The city's authorities were convinced that a non-strategic city with a large number of military hospitals, POW compounds, etc., would not receive anything approaching the annihilative smashing so many other cities and towns had undergone. Therefore most of the air defense and flak batteries that would otherwise be in Dresden were transferred to areas where it was assumed they'd be needed. In The Bomber Command War Diaries the basic facts of the February 13-14 Dresden raids were recounted: "796 Lancasters and 9 Mosquitoes were dispatched in two separate raids and dropped 1,478 tons of high explosives and 1,182 tons of incendiary bombs... 311 American B-17s dropped 771 tons of bombs on Dresden the next day, with the railway yards as their aiming point. Part of the American Mustang (P-51) fighter escort was ordered to strafe traffic on the roads around Dresden to increase the chaos. The Americans bombed Dresden again on the 15th and on March 2 but it was generally accepted that it was the RAF night raid which caused the most serious damage." Of the American strafing Irving noted: "British prisoners who had been released from their burning camps were among those to suffer the discomfort of machine gun attacks... Wherever columns of tramping people were marching in or out of the city they were pounced on by the fighters, and machine-gunned or raked with cannon fire."

One RAF Flight Engineer recalled that the brightness of the fires below allowed him to fill in his log sheet by the light that shot skyward. A crewman of another plane wrote: "I confess to taking a glance downward as the bombs fell, and I witnessed the shocking sight of a city on fire from end to end. Dense smoke could be seen drifting away from Dresden, leaving a brilliantly illuminated view of the town. My immediate reaction was a stunned reflection on the comparison between the holocaust below and the warnings of the evangelists in Gospel meetings before the war." David Irving noted that "In many cases during the night raids, people, finding that dense suffocating fumes from above were rolling down into the unventilated basements, broke down the wall breaches. Thus the smoke had access to the next-door cellars as well." One survivor wrote: "The detonations shook the cellar walls. The sound of the explosives mixed with a new, strange sound, which seemed to come closer and closer, the sound of a thundering waterfall; it was the sound of the mighty tornado howling into the inner city." Retired Major James "Knobby" Walsh was an Army Air Corps bombardier in WWII and is a subscriber to The Barnes Review. He forwarded the following passage from Edward Jablonski's Airwar - Wings of Fire (Doubleday & Co.): "The horror and the terror on the ground was incredible, destruction was extensive, and the loss of life was frightful. The beautiful little city, its population swollen by an influx of refugees from the east fleeing before the Russians bent on revenge, pillage and rape, and its predominantly wooden buildings, ideal for incendiaries, all but vanished in a howling whirlwind of incineration. Although it is unlikely that the true toll will ever be known, the number of people probably killed at Dresden was about 135,000 [as compared with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, which killed 71,379]."

In The First Casualty Knightly wrote: "The flames ate everything organic, everything that

would bum. People died by the thousands: cooked, incinerated or suffocated. Then American

planes came the next day

to machine-gun survivors as they struggled to the banks of the Elbe." Knightly added that

"Precise casualty figures will never be known. The German authorities stopped counting when

the known dead reached 25,000 and 35,000 were still missing.

Some post-war sources put the number of dead at from 100,000 to

130,000, which would greatly exceed the number killed in

the atom-bombing of Hiroshima... Dresden was merely a staging center for a half million

refugees from Silesia. The [rail] yards were not even attacked. There were no ammunition

workshops and factories, only a small works making optical lenses for gunsights."

. Part 3 Aftermath: Coverups and Lies The horror extended well into the aftermath, with countless thousands lacking a bare subsistence food ration in addition to adequate winter shelter. Tens of thousands with various degrees of burns and other injuries went unattended.

Fully realizing the extent of the destruction and the circumstances under which it was meted out, London moved to cover its position even before the follow-up American raid. At 9 am on February 14 the Air Ministry released a full-length bulletin. Irving wrote: "In a statement describing the target city in unusual detail, the Air Ministry stressed the vital importance of Dresden to the enemy: As the center of a railway network and as a great industrial town it had become of the greatest value for controlling the German defenses against Marshal Koniev's Armies." Knightly pointed out that Ministry of Defense records show that no war correspondents flew with the bombers, and that there were no eyewitness accounts save for "a few air crews interviewed on their return, and they were given various concocted explanations as to why they were bombing the city - they were attacking German army headquarters, destroying an arms dump, knocking out an industrial area, or even 'wiping out a large poison gas plant.'" From The First Casualty: "The truth first came out in Sweden. At 10:15 am on February 15 a Swedish news bulletin transmitted in Danish to occupied Denmark said that the death toll in Dresden was already between 20,000 and 35,000." Then newspapers in neutral countries began printing stories of the raid. On February 17, the Associated Press

Despite the incredible chronological inaccuracy of the "long-awaited decision," the Dresden story, basically, was out. But British censors placed a solid clamp on the true nature of Dresden. They fed the Fleet Street press the official "major strategic target" line. Thus following the raid, readers of the Evening Standard read the lead story, under the headline "The Blasting of Dresden" and accompanied by a front page picture of bombs dropping on indistinguishable targets, without learning anything the government wished withheld. In America, however, millions registered feelings of rage, disillusion and concern. Marshall's statement that the raid was staged at Stalin's request set off some anti-administration sentiments in Congress. But overall, Roosevelt's bitter enemies were wary of exposing themselves to accusations of criticism during wartime, a factor that had severely curtailed the Dewey-Bricker Republican ticket in 1944 when FDR won his fourth term. In volume three of The Army Air Forces in World War II, published by the University of Chicago press, it was stated that "General Arnold was disconcerted about the publicity" that the AP story had generated and that "Eisenhower heard all about the issue, and AAF headquarters, aware of the damaging impression the recent publicity had made, took steps to prevent another break." England's Fleet Street blackout did not prevent members of Parliament from becoming privy to Dresden's slaughter. Many MPs, especially those who had fond memories of the city, reacted with outrage. Churchill, the holocaust's ultimate button-pusher, became the target of considerable friendly fire. In Bomber Harris Saward noted that "The whole question of the Allied bombing policy suddenly came under question." In March, Churchill wrote the Chiefs of Staff: "It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing the German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed." Saward found it amazing that "Churchill, of all people" would reach this conclusion in the wake of severe criticism. He noted that the PM "had been the greatest proponent of destroying Germany city by city..." Few today realize that in early 1945 the U.S. carried out from England six robot missions of B-17s, each loaded with 10 tons of explosives. The planes were "war weary" craft that had been stripped of armor and armament. Pilots got the drone bombers airborne and pointed toward their German targets, then bailed out. None had been successful in hitting specific targets, and the project was scrapped due to British objections. Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal had expressed fears that the Germans, with a great number of planes but few surviving pilots, would be tempted to reply in kind. As to the German V-1 and V-2 rocket bombs that fell on England in 1944, few dispute that they were aimed at strategic targets but that there were a large number of civil casualties. Following the war, involved American and British air commanders would fudge and rationalize the years of day-night civilian slaughter. A B-17 navigator, now a lawyer in Northern Virginia, recalls that in raiding Munich their PMI (Point of Maximum Impact) target was the large fountain in the center of the city's business district at high noon, "in order that we could catch the most people out at lunchtime." But "Bomber" Harris remained unmoved by the slaughter, devastation of cultural landmarks and public criticism. The Cromwellian commander raged against any diversions of Bomber Command's mission. In a March 29, 1945 letter to Air Vice Marshal Sir Norman Bottomly, Harris wrote: "The [public] feeling, such as there is, over Dresden could easily be explained by a psychiatrist. It is connected with German bands and Dresden shepherdesses." And in writing Bottomly, a man who knew all the grim details of the Dresden reality, Harris prompted the question of who might better benefit from the ministrations of a psychiatrist: "Actually Dresden was a mass of munitions works, an intact government center, and a key transportation point to the East. It is now none of these."

However, Harris was seen quite differently by America's two most celebrated figures of that period. In a July 13, 1945 letter that went well beyond cordial recognition, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote Harris: "My gratitude to you is a small token for the magnificent service which you have rendered, and my simple expression of thanks sounds totally inadequate. Time and opportunity prohibit the chance I should like to shake you and your men by the hand, and thank each of you personally for all that you have done." On October 17, 1944 Harris had been awarded America's Legion of Merit with the degree of Chief Commander. The citation concluded: "He performed his complex task with inspiring leadership and with outstanding cooperation, skill and determination, reflecting great credit upon the service he represents and upon the Armed Forces of the United Nations. [Signed] Franklin D. Roosevelt."

As with Cromwell in Ireland and Roberts and Kitchener in South Africa, Sir Arthur Harris had broken their walls. But he had not broken their courage.

Holocaust at Dresden |